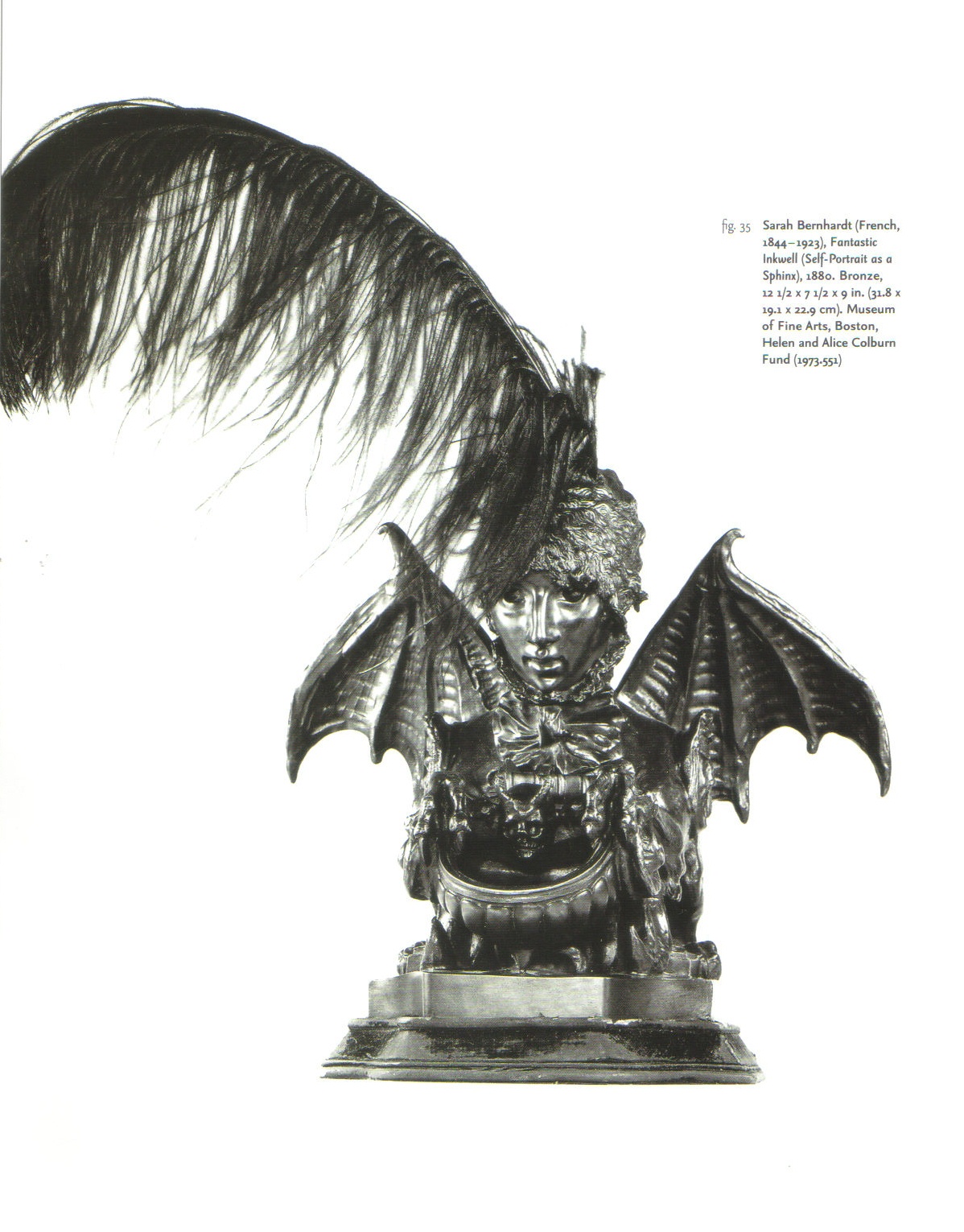

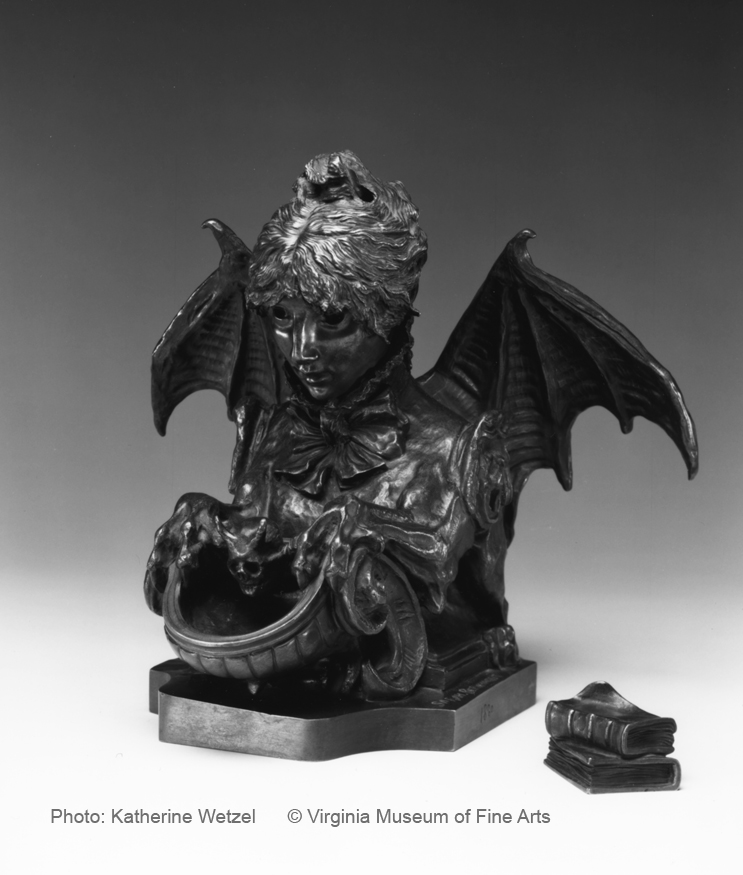

7 ¾ in (20 cm) high, 8 ¼ in (21 cm) wide, 7 ¾ in (20 cm) deep

Provenance

Citadelle Vauban, Belle-Ile, France

cf. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Romantics to Rodin, French Nineteenth-Century Sculpture from North American Collections, 1980, pp.141-143

Carol Ockman and Kenneth E. Silver, Sarah Bernhardt: The Art of High Drama, exh. cat., The Jewish Museum, New York, 2005, p.50, fig.35

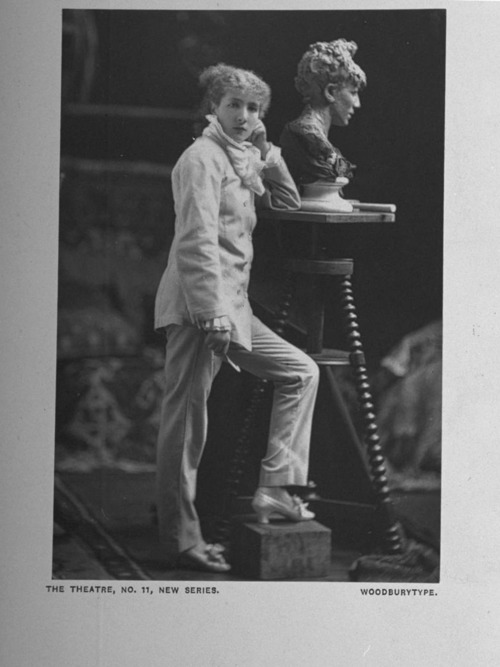

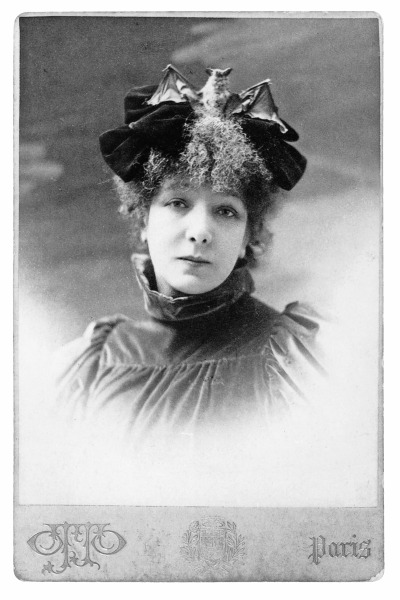

Bernhardt embraced the idea of total performance, as much off the stage as on it, and she welcomed the chance to enhance her image further through the decorative arts. In 1869, she began training as a sculptor and painter under the tutelage of the sculptor Roland Mathieu-Meusnier (1824-1876), taking advice from others too, including Doré. In 1875, the Salon in Paris accepted several of her portrait busts and awarded her an honourable mention. Her first showing of work in London took place in 1879, and it was here that a cast of this inkwell (titled Encrier Fantastique) was first exhibited. The piece was widely admired and a cast was later acquired by Queen Mary. Another was also displayed in 1880 at the Union League Club in New York. This last may well be the cast that is today kept in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Both these are of a slightly larger size than this one. Another larger version is held in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

This sculpture captures the darker, more bizarre and unsettling elements of Art Nouveau which Bernhardt sought to channel both in her performances and in her own life. The theatre critic, Jules Lemaître, described her as a ‘distant and chimerical creature, both hieratic and serpentine, with a lure both mystic and sensual’, like that of ‘Salomé, Salammbo, or of fantastic queens of Gustave Moreau’. The masks of tragedy and comedy on her shoulders signify her profession as an actress, and also make a connection between this piece and a role she was playing at the time. In 1879, she was rehearsing the role of Blanche de Chelles in Le Sphinx by Octave Feuillet. This character was the quintessential femme fatale, with her sphinx-shaped poison ring, and may well have inspired Bernhardt in her fashioning of this sculpture. Bernhardt clearly embraced this role, enjoying portraying herself as an almost otherworldly creature, around which her admirers gathered, eagerly seeking to understand her, yet always finding her just out of reach.

This important sculpture comes from the Citadelle Vauban museum in Belle-Ile, France, which closed in 2010. The citadel was first constructed as a fortress by François de Rohan in 1549, under the direction of Henry II of France. Marshal Sébastian Le Prestre de Vauban (1633-1707) was primarily responsible for creating the citadel that remains today. Beginning in the mid-19th century, many artists, musicians, writers and actors were attracted to the wild beauty of the coast of the Citadelle Vauban. Matisse and Monet, Honegger and Flaubert were among those who frequently visited the island.

Sarah Bernhardt first came to Belle-Ile in the summer of 1894, at the height of her fame. Every summer she chose to reside on the Pointe des Poulains, at the extreme northern tip of the island in an abandoned Second Empire fort, looking out over the sea. Having purchased this property, she went on to build two white villas to house artist friends such as Clairin, Rostand and Reynaldo Hahn as well as other celebrities eager to partake in the cult of ‘The Divine’. Like a liturgy, her days on Belle-Ile followed a carefully written score with fishing, painting, napping and readings of new plays in a carefully staged existence barely ruffled by the cries of anger or joy from the ‘golden voice’ ringing out amidst the thunder of the waves.